Scholarly Study of the

Music of Keith Emerson (1944-2016).

British keyboardist Keith Emerson (1944-2016) was best known for his work with the 1970’s progressive rock band Emerson, Lake and Palmer (“ELP”). He also composed a serious piano concerto (recently re-recorded by prominent concert pianist Jeffrey Biegel), multiple film scores (including “Nighthawks” for Sylvester Stallone), and various other compositions in a wide variety of styles and settings. He’s even jammed with jazz great Oscar Peterson as a featured guest on the latter pianist’s TV show in the 1970’s.

For decades I have been fascinated by the unique sonorities, musical textures, and boldly shimmering dissonances that resonate in Emerson’s music. Despite his unique talents as a keyboardist and composer, the fact that he was in a popular “rock band” in the 1970’s, sometimes brings dismissive eye rolls to some musical snobs.

The intent of this page is to discuss, at a surface level, some of Emerson’s musical innovations. Yet I do acknowledge that the casual or more prudish observer of Emerson’s legacy may wish to ignore some of the “baggage” that he brought on himself as a non-singing keyboard player—extramusical things he did in efforts to gain audience attention as a keyboardist in a guitar-oriented rock music world:

Although quiet, soft-spoken and articulate off stage, onstage Emerson was a self-described egomaniac; he did not rely only on his musicianship to get a crowd’s interest. In at least one concert in mid 1970’s he was strapped via a seat belt to the piano bench and “played” a grand piano that literally spun circles above the stage. Many performances featured the dramatic “destruction” of his Hammond L-100 organ (in a keyboard parallel of what Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townsend did with their guitars and what Keith Moon did with his drums in that era). His suggestive low-brow extra-musical antics with the Moog Ribbon Controller are, to this writer, a bit embarrassing, but they reliably got the rock and roll audience reaction he sought. Also, with his previous band “The Nice,” Emerson once burned a large drawing he made of an American flag onstage at the Royal Albert Hall in London as they played their version of Bernstein’s “America” during Vietnam War times. That particular event got him blacklisted from performing at this prestigious venue for a couple decades afterward.

Despite the aforementioned antics, the ELP concert I attended as a teenager on January 24th 1978 (there is a link to the audio of that performance below) contained various extra-musical performance elements that had a lasting dramatic impression on me. For one, his giant Moog synthesizer “exploded” in a bright flash of light and smoke during “Great Gates of Kiev” as the sequencer accelerated to impossible speeds during a musical climax. Another element was his jovial consumption, over the course of the concert, of a complete bottle of some liquor or wine he kept within reach (which, between swigs, he repeatedly plopped on top of his $50,000 Yamaha GX-1 synthesizer). This bottle was almost another character on the stage during the show. The crowd cheered as he took each giant swig, often while another hand nonchalantly played complex keyboard parts.

But the bottom line is that Emerson could PLAY. He did not need any of the above “rock and roll behaviors” to gain my respect. The integrity of his musicianship as a composer/improviser/performer was substantial. He was a complete, self-sufficient pianist, organist, and pioneering synthesist, blessed with prodigious musical chops and creativity. He was a musician who combined rock with classical and jazz styles effortlessly. Emerson often improvised a musical continuum of musical lines in a brilliantly impetuous kaleidoscope of styles ranging from bebop to mellifluous to ethereal to intellectual, often over creative and mesmerizing minimalistic quartal left-hand ostinatos. He was also entirely comfortable with standard self-accompanimental stride, rootless comping, unusual meter signatures, and practically every jazz and rock style up to the 1970’s. His harmonic language that emphasized quartal aspects was, and remains, unique in the world of popular music.

Seeing Emerson Lake and Palmer as my first concert was an influential experience. The three members together, in the 1970’s, produced a musical synergy befitting of a whole cast of musicians.

There is arguably more depth and individuality to Emerson’s musicianship than any other successful rock instrumentalist. Let’s talk some specifics: His harmonic and melodic language uniquely celebrates the interval of the perfect fourth. He was known to boldly add a perfect fourth to major chords, voiced either a minor second above, or a major seventh below the third of the chord. Major chords with the arbitrarily added fourth are a hallmark of his harmonic style—an unusual sonority that Emerson used fairly commonly. What influenced him to implement this sound as early as he did and as often as he did? This is a primary shimmering dissonance that, to this writer, makes his output all the more fascinating.

Emerson had a predilection for all added-note chords, quartal and quintal harmony, open 5th chords, and chord voicings consisting of wide intervals juxtaposed with seconds. Abundant use of extended jazz harmony, Lydian, Lydian-Dominant, Dorian, and occasional whole-tone scales in his improvisations brought an added sophistication to his output.

But the interval of the fourth, both in its melodic and harmonic forms, is the crux of Emerson’s style. The multimovement work “Tarkus” could be argued to be the ultimate celebration of both the interval of the fourth and the sus4 (suspended 4th) chord.

Of course, Emerson was not the first to use quartal voicings—composers from Debussy to Charles Ives experimented with this harmonic language. Many jazz musicians of the 1960’s, including McCoy Tyner, developed that harmonic style into their musical identities. Emerson was an astute follower of such sounds within jazz. He worked assiduously to learn the musical vocabulary of jazz performance. He made the various sounds of stacking 4ths integral to the idiom of progressive rock, and thereby influenced Rick Wakeman, Eddie Jobson, Patrick Moraz, and others, who brought these sounds into the forefront of their own musical vernacular.

Emerson was also interested in many “classical” composers, from Bach to those of the twentieth century. He was able to capture the various musical energies created by contemporary composers’ utilization of dissonance, and let that knowledge inform his own compositional and improvisational work.

On the other hand, Emerson was also a contemporary of the guitarist Jimi Hendrix. Their respective bands had both toured alongside each other in the late 1960’s, and they shared a kinship. Emerson’s later performances with the rock band Emerson Lake and Palmer fused the complex, sophisticated quartal harmonic and melodic languages of jazz and modern classical music with the raw energy of Hendrix’ rock performances. This scattered and unlikely cocktail of disparate influences, coupled with Emerson’s fertile improvisational mind and cornucopia of “chops,” brought a unique sound to the ears of a popular audience.

Regarding his technique at the piano, one could say that Emerson’s left hand worked harder than most keyboard players’ right hands. In his piano improvisations, as mentioned earlier, he often used ostinato patterns in the left hand as a springboard for right-hand improvisation. His right hand adeptly played a great deal of bebop jazz vocabulary, which he would intermingle unusual and complex melodic sequences, and any number of quartal, blues, pentatonic ideas, or simple quotes of recognizable material. Often he would go for bombastic dissonances that he would work out in clever musical ways to justify their appearances. He had an active improvisational imagination.

In regard to pioneering his use of the Moog synthesizer, Emerson nearly singlehandedly defined the sounds and styles of the early 1970’s that others would emulate. (Interestingly, The Monkees were the first popular group to record with a Moog, and The Beatles used a Moog in various tracks on Abbey Road). Rick Wakeman of the band Yes was also one of the pioneers of the Moog, but Emerson led the way to making its sound a central character in the rock idiom. One need only listen to the end of “Lucky Man” or any number of places in their live recording of “Pictures at an Exhibition” to experience the distinctively dramatic, declamatory, and ethereal moods Emerson would create.

In 1988 Blair Woodward Pethel, at the Peabody Conservatory, wrote a dissertation on Keith Emerson’s music entitled Keith Emerson: The Emergence and Growth of Style: A Study of Selected Works. This important document brought an academic validity to the “serious” aspects of Emerson’s music. The gravitas of Emerson’s influence was now firmly established, as Pethel’s dissertation was a gateway to the legitimacy of the study of Emerson’s output. Prior to that time, despite a limited amount of discussion of ELP in the New Grove Dictionary of Music (under “popular music”), and Emerson’s composition and recording of his Piano Concerto No. 1, which toured with a full orchestra, most people in the classical world seemed to acknowledge Emerson only with rolling eyes as a pop music artist who occasionally did wild stage antics.

Emerson had also gained a reputation as the quintessential Hammond Organist in rock music, except his compositions and improvisations were generally so complex and difficult that others were unable to recreate what he played. Most rock keyboardists did not even try. Some of his music was (thankfully) published, but to this day, much of his material is only available in transcriptions, some of excellent quality, and some of dubious accuracy. Emerson’s entire concept of how to play the Hammond was unique.

In a reception parallel to that of the classical world, many jazz aficionados saw Emerson’s work with the Hammond organ as an aberration of “true” stylistic practices. Traditionally, Hammond players like Brother Jack McDuff (who Emerson idolized) and Jimmy Smith, confined their output to jazz and bebop “standards” using swing and Latin patterns, primarily playing bass lines with their left hand (and some with their feet). In the traditional jazz organ trio style, at any given time the right hand either comps chords or plays melodic lines (generally opposite what the guitarist in the trio is doing). By contrast, Emerson sometimes played Moog bass while Lake played guitar, but more often played Hammond in a more contrapuntal fashion while Lake played electric bass, or Emerson would simply double Lake’s bass lines. Sometimes Emerson simply played open 5ths in his left hand. Many jazz Hammond musicians might have interpreted Emerson’s methods as a vapid abandonment (or even a gross misunderstanding) of jazz tradition, when in reality he was simply doing things in his own sui generis style.

Pethel’s writing points out that Emerson’s performance style was a unique and substantive amalgamation of classical, jazz, and rock. It seems people of both classical and jazz disciplines would not take Emerson seriously because of his participation in the other two categories. Many in rock circles were similarly uncharitable in their opinions toward Emerson, feeling the purity of a simple rock style was diluted by his clever interpolations of jazz and classical elements.

His “classical” quotations brought serious music to the ears of a rock audience (including to this writer). In 1971 Emerson Lake and Palmer’s first live album consisted of their rock arrangement of Mussorgsky’s monumental suite “Pictures at an Exhibition.” The energy and surfeit of moods they brought to the piece cover the gamut of emotion and musical excitement, and it was done effectively with three individuals on one stage in one evening. There are many additional examples of the influence of serious music in his performances.

Emerson masterfully interpolated J.S. Bach’s “Allemande” from French Suite No. 1 into “Knife Edge” from Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s first album. This added musical profundity and gravitas to what might be considered the Development Section of an otherwise dystopian pop tune. (Other parts of the same song are structured around a riff based on Janacek material). Additionally, the first section of Bach’s Prelude in D minor from the Well-Tempered Clavier (up to the cadence in the relative major) appears briefly in a beautifully-executed third-stream setting in an interior section of “The Only Way” from Side Two of “Tarkus.” Bartok’s “Allegro Barbaro” provides the genesis of the opening track of their first album. Aaron Copland’s influence is also represented in multiple ELP recordings (Copland even made positive statements regarding Emerson’s use of his music), as is the work of Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera.

The opening orchestral strings in Emerson Lake and Palmer’s 1977 epic piece “Pirates” were written as a nod to Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring.” This thirteen-minute sonic diorama utilizes the Paris Opera orchestra, sonically painting Emerson’s unique, shimmering quartal and quintal harmonic style in a fully-orchestrated setting along with the rock trio, with Emerson playing Yamaha’s GX-1 synthesizer throughout. Before its release, Leonard Bernstein himself was given a private hearing of “Pirates” as it was being mixed in the studio. Bernstein also heard Emerson’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in the same sitting (although his brief comment about this piece was cryptic and somewhat laconic). This recording was followed up with a tour that included a 70-piece orchestra. When the band realized how financially draining it was to use the orchestra (I seem to recall reading somewhere that it was $70/minute) their accountant forced them to drop the orchestra, and they toured as a trio again to recoup costs. Emerson’s subsequent live score reduction of this huge orchestral piece is impressive.

As a Progressive Rock band, many of Emerson Lake and Palmer’s compositions were complicated, lengthy, and featured multiple contrasting sections, often showcasing complex meters. The first third of the track “Trilogy” (from the eponymous album) is essentially a delicate and beautifully-crafted baritone voice/piano art song of the late romantic idiom. This piece would probably receive serious performances in the academic and conservatory world, except that its through-composed form morphs unavoidably into high gear (adding drums, bass, and emphatic synthesizer solos over a 5/4 ostinato before moving to other “rock” sections), not allowing for the closure of an idiomatically-appropriate conclusive cadence in the beautiful, thoughtful, and delicate style in which it began.

Abrupt and contrasting stylistic juxtapositions in ELP’s compositions and performances manifested the deep musical competence and creativity of the players in the band, but the same musical gestures challenged the attention span of some casual rock listeners. Ironically these same aspects provided a legitimacy of the sophistication and further intellectual potential of the musical idiom for others. British bands like Yes, U.K., Jethro Tull, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and (early) Genesis were other British bands that worked in a parallel fashion. Kansas and Rush were two bands from North America that followed suit in the Progressive Rock style. (Rush with a heavier guitar-oriented sound). Todd Rundgren’s Utopia is another band that contributed to this category.

My interest in Emerson’s output, and my personal dissatisfaction with most other authorities’ answers to my questions about his music led me to study his music on an academic level. Upon entering graduate school in the late 1980’s, as a result of the new legitimacy of Emerson’s music provided by Pethel’s groundbreaking dissertation, I was eventually able to convince my thesis committee at Indiana State University to allow me to write my master’s thesis on side one of the Emerson Lake and Palmer album “Tarkus.”

My thesis is entitled “The Compositional Style of Keith Emerson in ‘Tarkus’ (1971) for the Rock Music Trio Emerson Lake and Palmer.” Within this document I applied traditional “classical” analytical concepts (which required some atonal theory) to complete an analysis of the “Tarkus” suite, which takes up side one of the eponymous album.

If one were to look up “Tarkus” in Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tarkus they will find a link to my 149-page thesis at the “Further Reading” section near the bottom of the page.

I am deeply humbled to hear that my analysis further “legitimizes” Emerson’s music to “classical” academia, and am additionally happy that my thesis has taken a life of its own, providing references for others’ academic study that have followed. It is gratifying to me that Giuseppe Lupis’ later doctoral dissertation on Emerson’s music “The Published Music of Keith Emerson: Expanding the Solo Piano Repertoire” makes various references to my thesis:

https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/lupis_giuseppe_200605_dma.pdf

p. 6: “In Chapter VII of his Master of Arts thesis, “The Compositional Style of Keith Emerson in Tarkus (1971) for the Rock Music Trio Emerson, Lake & Palmer,” Peter T. Ford observes that The Battlefield is the only movement in which Emerson did not contribute officially to the composition. However, because Ford’s statement and detailed analysis suggest that the same hand is behind the whole suite, it is possible to assume Emerson’s heavy participation in the writing.”

p. 13 (footnote): “Tarkus has been thoroughly analyzed by Peter T. Ford in his Master’s thesis “The Compositional Style of Keith Emerson in Tarkus (1971) for the Rock Music Trio Emerson, Lake and Palmer.””

p. 15 (footnote): “Keith Emerson’s compositional style has been thoroughly discussed…in the 1994 Master’s thesis by Peter T. Ford…”

Scholar and saxophonist Woody Chenoweth’s 2019 doctoral research paper from Arizona State University includes, among discussion of other pieces written for saxophone quartet, discourse regarding my saxophone quartet arrangement of ELP’s “Tarkus” (which was first recorded by Sax 4th Avenue, and has been performed by other groups, including the “Tsukuba Saxophone Quartet” in Japan, and Woody Chenoweth’s own Cincinnati-based saxophone quartet, the “Shredtet.”

In addition to the study of my saxophone quartet arrangement nearer the core of his paper, I am deeply humbled to see a lengthy questionnaire/interview of me as a composer and as the arranger of this piece as one of the focuses of Dr. Chenoweth’s research. This questionnaire/interview of me as arranger (and related topics as a composer) covers on pp. 73-88 of his thesis (pp. 81-96 of the PDF).

The link to his doctoral research document is here:

https://repository.asu.edu/attachments/217045/content/Chenoweth_asu_0010E_19064.pdf

Another study that references my work; this writer emphasizes different aspects of symbology, but nevertheless they cite my thesis:

Emerson’s musical output continues to be rich with potential for further academic study. I still have many unanswered questions about his music—but that is what makes it so interesting. It is my hope to see additional future scholarly papers and academic investigation into Emerson’s important and deserving musical legacy.

Maybe you have something to contribute to the literature?

Above: some visual electronic artifacts from my on-camera interview in April 2019 in British Columbia by David and Jason Woodford regarding an academic view of Emerson’s compositional style.

I was deeply honored to be one of many individuals interviewed on camera for the documentary they are producing on Emerson’s legacy (fingers crossed that it gets released). Many of the other individuals interviewed for this are luminaries in the progressive rock world. Although Emerson himself was part of the initial documentary project, sadly, his sudden unexpected passing in March 2016 interrupted the process. I am DEEPLY honored to have been asked by the Woodfords for my limited participation in this important historical documentary. In my opinion, its title “Pictures of an Exhibitionist,” much like other aspects of Emerson’s career, detracts from the seriousness of Emerson’s musical prowess, but nevertheless, I am hoping to see the documentary released.

** Sad Addendum**

David Woodford passed away in the fall of 2022. He and his family have been so delightful to me, and David will be deeply missed. Rest in Peace.

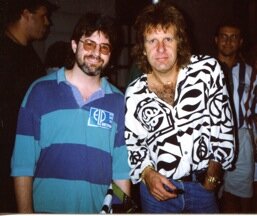

Meeting Keith Emerson for the first time in Cincinnati, 1992, while writing my master’s thesis.

Bruce Pilato, Carl Palmer’s manager (formerly Greg Lake’s manager; a man who has worked with musicians such as Ringo Starr and countless other luminaries of the rock world) kindly takes the time to pose with me in Kent, Ohio November 2021 on a Carl Palmer tour.

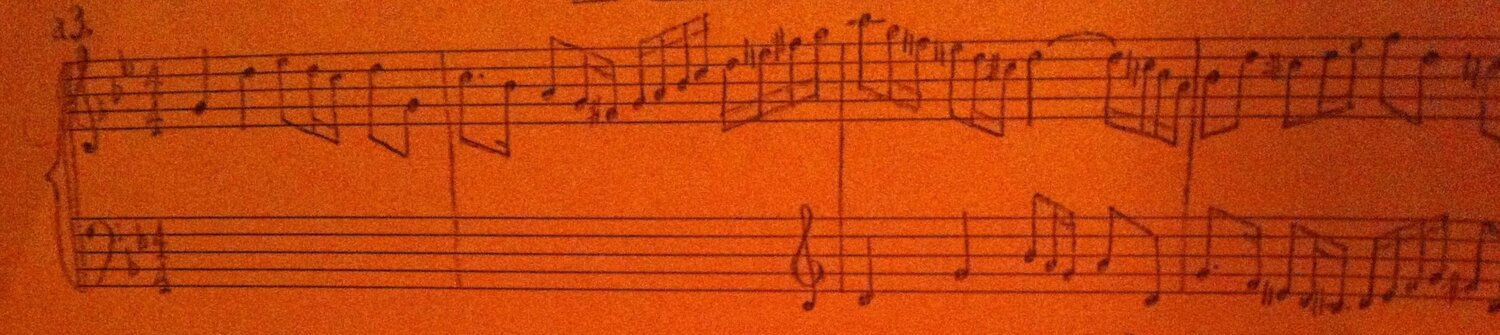

Above the image with Bruce Pilato: Page 68 (of 149) from my thesis on Emerson’s Compositional style in Tarkus. This is part of my analytical breakdown of the enigmatic 24-note descending atonal flourish that begins the third movement, entitled “Iconoclast.” Upon casual perusal, the intervallic patterns seem almost aleatoric, and Emerson only uses eleven notes of the chromatic scale. Closer inspection reveals that his descending run contains not one, not two, but three “mirrors” of exact intervallic sequences, two of which overlap.

Further, if the downbeat of the following measure is included, the middle of the mirror of the middle sequence falls within a “Golden Section” demarcation. That proportional aspect could simply be coincidental, but the intervallic mirror inversions nevertheless indicate evidence of careful and deliberate calculations on the composer’s behalf. On top of that, it is not easily to play quickly.

All of this for a rock album? What was his creative compositional mind thinking when he chose these notes in aggregate? I regret that I never got to ask Emerson what he was thinking when constructing this awkward-to-play blip in musical time. Clearly, he must have focused great attention to compositional detail in this very brief (probably three seconds) connective segment of music.

Epilogue to this page: In late summer 2020, I discovered a YouTube recording of an evening that had great profundity regarding my future: My sister, who was a college student at Indiana State University, took her two little brothers—me (age 13) and my high-school-aged brother to Hulman Center on January 24th 1978 to see Emerson, Lake and Palmer in concert. (My ticket was $6, and that was a lot of money at the time).

This concert made me decide piano lessons are cool and playing in a band was even more cool. This is the recording of their concert that evening. It is unique and profound to me to get to re-hear the actual event that defined my choice of fields to study. I hope you enjoy this as much as I enjoyed finding it on the internet: